BUDDHA AND BUDDHISM

1) FROM GAUTAMA TO BUDDHA:

The recluse Gotama is lovely, good to look upon, charming, possessed of the greatest beauty of complexion, of sublime color, a perfect stature, noble of person”.

This was the way Canki, a highly respected Brahmin leader and a contemporary of Siddhartha described the physical appearance of the Buddha. Other accounts also attest to a majestic, charismatic appearance of the Buddha in his early years. Without a doubt, he was also a great teacher and one who could influence almost any body by his compassion and his persuasive abilities. And across the millennia and transcending national boundaries, Gautama the Buddha still exerts influence on people of all nationalities and racial extractions. Indian Philosophical thought was and continues to be profoundly influenced by his thoughts.

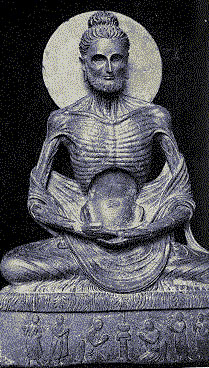

Gautama the Buddha in a Meditative Pose

Unique among religions, Buddhism does not profess sin and punishment or penance, it abhors caste system and above all, this religion (along with Jainism) is not based on a belief in a Supreme Being or Soul.

“GAUTAMA THE BUDDHA” (Gautama the Enlightened one) 563-483 BC:

The Buddha was born as a Prince in the Kingdom of the Sakyas near the border of present day Nepal and India (but in ancient India) on the full moon of the month of Vesaka (May). The place of birth was Lumbini, a park that his mother the queen passed on her way to her parents’ house in Devadaha. There, in a curtained enclosure, she gave birth to a boy; the place of his birth is marked by an “Ashoka Pillar” (erected in the 3rd century BC by Emperor Ashoka).

A dream his mother had the night before his birth foretold of the birth of a son who would either become a universal king or a Buddha. The sage Asita (also called Kala Devala) who was the teacher and religious advisor of the King Suddhodana, upon seeing the child and perceiving auspicious sights on his body, predicted that the boy will one day become a Buddha. Also, on the fifth day of his birth, during the naming ceremony, out of the 108 Brahmins (priests) present, seven of eight specialists in interpreting bodily marks prophesized that if the child remained at home he would become a universal monarch; however, if he left home he would become a Buddha. The child was named Siddhartha (in Pali, Siddhatta) which means “one whose aim is accomplished”. The ancient Buddhist literature has recorded another event when Siddhartha was a small boy. His father had left him with the nurses and gone to attend a local plowing festival. The nurses, distracted by the festivities, had left the boy alone for a short period. When the King returned, he found the boy seated under a ‘jambu’ tree in a ‘dhyana’ (meditation) pose, cross-legged and in a trance. The King knelt down in worship upon witnessing this awe-inspiring sight.

THE EARLY YEARS:

Seven days after his birth, Siddhartha’s mother Queen Mahamaya died and the child was brought up by her sister Mahaprajapati Gautami, as his father married her. In order to keep the prince happy and contended so that he will not leave home, the King lavished luxury on him. In the Buddha’s own words:

“Bhikkhus (monks), I was delicately nurtured, exceedingly delicately nurtured, delicately nurtured beyond measure. In my father’s residence lotus-ponds were made, one of blue lotuses, one of red and another of white lotuses, just for my sake…Of Kasi cloth was my turban made; of Kasi my jacket, my tunic and my cloak…I had three palaces: one for winter, one for summer and one for the rainy season. Bhikkhus, in the rainy season palace, during the four months of the rains, entertained only by female musicians, I did not come down from the palace.”

At the age of 16, he married his cousin, princess Yasodhara. Neither the marital bliss nor the luxury that was showered on Siddhartha completely satisfied his restless mind. Like other members of the aristocracy he had worldly weaknesses such as drinking alcohol and entertaining many concubines. Thus, when he was 29, for the first time in his life Siddhartha was exposed to human suffering. These “four signs” were as follows:

1) When he was outside the palace grounds he saw ‘an aged man, as bent as a roof gable, decrepit, leaning on a staff, tottering as he walked, afflicted and long past his prime.” Up to that time the prince has never seen an old man (so the story goes) and when questioned, his charioteer and companion told him that he was old and that all men were subject to old age, if they lived long enough.

2) Another day the prince saw “a sick man, suffering and very ill, fallen and weltering in his own excreta, being lifted up by some…” His charioteer again explained how people were subject to sicknesses.

3) Another day he saw a dead body and was told that everyone ended their lives in this manner eventually.

4) He saw a “shaven-headed man, a wander who has gone forth, wearing the yellow robes. The prince was impressed by the man’s peaceful and serene demeanor and this made his mind up in trying to wander out in the world to discover why the man displayed such serenity in the midst of misery.

THE RENUNCIATION:

Siddhartha decided to renounce his princely life and, after quietly bidding farewell to his wife who was asleep, he left the palace with his charioteer and companion, Channa. During that night they traveled on horse-back until by dawn they crossed the Anoma River. There Siddhartha gave all his ornaments to Channa, wore the cloth of ascetics and was thenceforth he was known as Gautama (Gotama in Pali). He traveled south to places renowned as centers of learning. He sought-out great teachers such as Alara Kalama and Uddaka Ramaputra. He quickly mastered all the mystical systems that they knew but was not satisfied. Finally, he arrived at a beautiful village in the Magadha County, where he met five ascetics. This village was called Senarigama, near Uruvela and they settled down to search for truth in earnest. What followed were severe austerities and extreme self-mortifications. After six years of such austerities Gautama was near death. The result of the austerities was described by the Buddha himself as follows:

A statue of the Buddha that depicts his appearance during the period of severe austerities

“Because of so little nourishment, all my limbs became like some withered creepers with knotted joints; my buttocks like a buffalo’s hoof; my back-bone protruding like a string of balls; my ribs like rafters of a dilapidated shed; the pupils of my eyes appeared sunk deep in their sockets as water appears shining at the bottom of a deep well; my scalp became shriveled and shrunk by sun and wind,…the skin of my belly came to be cleaving to my back-bone; when I wanted to obey the calls of nature, I fell down on my face then and there; when I stroked my limbs with my hand, hairs rotted at the roots fell away from my body…”

At the end of this period he became convinced that such severe self-mortifications will not lead him any closer to the truth. He abandoned such measures; in disgust, his five companions left him. Gautama started to take nourishment and recovered in due course.

ENLIGHTENMENT: (Gautama to the Buddha)

“My mind was emancipated; …ignorance was dispelled, Science (knowledge) arose; darkness was dispelled, light arose.”

Gautama next turned to meditation, usually under a banyan tree and he would meditate, cross-legged for long periods. The day before his enlightenment, he meditated at the base of a pipal tree (this tree is now called bodhi tree). He was determined to stay in meditation until he attained enlightenment. He encountered a determined effort by Mara, the tempter and lord of the world of passion to distract him and defeat his attempts to reach enlightenment. However hard Mara tried to distract Gautama he could not accomplish his goal. He finally gave up his attempts altogether and disappeared.

After defeating Mara, Gautama continued the deep meditation. It is recorded that during the period between 6PM and 10PM (of the night of his enlightenment), he gained the knowledge of his former existences. During the next four hours he attained the “Superhuman divine eye”, the power to see the passing away and rebirth of beings. During the period between 2AM and 6AM with more intense meditation he learnt the Four Noble Truths. Thus, at the age of 35, Gautama attained enlightenment and became the Buddha; this was the night of the full moon day of the month of Vesakha (May) in or around the year 528 BC. The place of this enlightenment is now called Bodh Gaya (or Buddhgaya), in Northern India and is one of the foremost attractions to Buddhist pilgrims from all over the world. The other main attraction is Lumbini, his birthplace where the Ashoka’s pillar is still present.

THE “MIDDLE PATH”:

After he abandoned the severe austerities and self-mortifications, the Buddha adopted the “Middle Path”, between the extremes of self-indulgence and severe self-mortifications. This middle path will lead to vision, knowledge, calmness, awakening and ultimately to Nirvana.

The Buddha gave his first sermon called “Dhammacakkappavattana-Sutta (“Setting in Motion the Wheel of Truth”), to his first five disciples at Isipatana, which is now called Sarnath, near Varanasi or Benares in the banks of Ganga and where now stands the famous Ashoka Pillar. At this sermon Gautama the Buddha described four “noble truths”. The first noble truth was that human existence is full of conflicts, dissatisfaction, sorrow and suffering. The second noble truth is that all these stem from man’s selfish desire. The third noble truth is that one can attain liberation or emancipation from these sufferings and lead to Nirvana. The fourth noble truth is described below as the “Noble Eight-fold Path” which is the way to the liberation.

The middle path is also known as the “Noble Eightfold Path” and consists of:

1) Right view

2) Right thought

3) Right speech

4) Right action

5) Right mode of living

6) Right endeavor

7) Right mindfulness

8) Right concentration

“BHIKKHUS” (DISCIPLES) AND SANGHA (COMMUNITY):

The first disciples of the Buddha were the five mendicants who left him in disgust when he abandoned severe austerities and self-mortifications. However, this was accomplished with some difficulty and after some serious discussions. Once they became convinced of his sincerity and believed that he had indeed attained enlightenment, they started to address him as “Lord”. Within three months, Buddha had converted 60 people and their disciples. These included Buddha’s own father, step-mother, son and his former wife. To this first group of disciples he spoke the following words, in preparation for sending them out into the world to spread his message of peace, compassion, wisdom and truth:

“Bhikkhus, I am freed of all fetters, both divine and human. You, too, are freed from all fetters, both divine and human. Wander forth, Bhikkhus, for the good of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world…Let not two of you go by one road. Teach the Dhamma (Dharma in Sanskrit) which is good at the beginning, good in the middle and good at the end….”

Another famous sermon the Buddha gave was to three famous ascetics and their many disciples, all of whom converted. This sermon, called “The Fire Sermon” dealt with the fire of lust, the fire of hatred and the fire of delusion. This Sutra is famous in the West as it formed the basis of Section III of the poem The Waste Land by the Poet T.S. Eliot.

The Buddha’s and his movement’s popularity soared and he converted scores of Hindus of all classes. Many women were also admitted into the order. This popularity brought with it jealousy among hostile sects and individuals. Prominent among the latter was a cousin and an uneasy disciple called Devadatta. When his request for naming him as the successor of the Buddha was turned down, he became openly hostile. At least 3 attempts to assassinate the Buddha were made but all of them failed. He then tried to create a splinter group; after this also failed, he became seriously ill and died.

The Buddha died at the age of 80. By that time the movement he started had spread far and wide within India and was on the verge of spreading to neighboring countries; however, the Buddha himself never traveled outside of India. His last spoken words were: “Then, Bikkhus, I address you now: transient are all conditional things. Try to accomplish your aim with diligence.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

1) Encyclopaedia Britannica, 18th Ed. 1989 Vol. 115, pp 268-74

2) www.nationmaster.com/encyclopedia/Buddhist

3) www.san.beck.org/EC9-Buddha.html

4) www.buddhist-temples.com/gautam-buddha.html

5) www.buddhist-temples.com/buddhist-religion.html

7) www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhistworld/buddha.htm

2) ESSENTIALS OF THE TEACHINGS OF THE BUDDHA:

The Buddhist Philosophy can be comprehended by considering the following segments:

1) SUFFERING AND ITS CAUSES:

The cornerstone of the Buddha’s teachings is that of human suffering. He stated that the existence itself is painful; the same conditions that make an individual also give rise to suffering. Individuality (a basic tenet of the Western psyche and which can be based on the notion of “I” and “mine”) implies limitation; limitation gives rise to desire; desire brings suffering.

2) IMPERMANENCE:

This suffering is caused by the fact that what is desired is often transitory, changing and perishing. It is this impermanence of the object of one’s desire that leads to disappointment and sorrow. The Buddha’s teachings are directed to removing the “ignorance” and thus guides to freedom from this suffering.

3) NONSELF (NONEGO):

The Buddha described the human existence as an aggregate of five constituents as follows:

a) Corporeality or physical form (“rupa”),

b) Feelings or sensations (“vedana”),

c) Ideations (“samjna”),

d) Mental formations or dispositions (“samskara”),

e) Consciousness (“vijnana”).

He argued that as the human existence requires all five of the above constituents and each of them in isolation will not form the self or soul without the help of the others, the Buddha termed this state as “nonself” or “nonego”.

4) KARMA:

Despite this notion of “nonself” or “nonego”, the Buddha taught that one carried one’s Karman from one life to the next. For example, good conduct is believed to bring pleasant and desirable results and bad conduct to lead to an evil result and repeated evil actions. This formed the basis for moral conduct to improve one’s lot.

However, the belief in “nonself “(i.e. absence of belief in a soul), while believing in repeated births and improving or worsening Karman have been attacked by non-Buddhist Philosophers. They question how a rebirth can take place without a permanent subject to be reborn. This argument remains unsettled.

5) FOUR NOBLE TRUTHS:

The Buddha formulated his “Four Noble Truths” to pave the way to removing the human misery. He described these tenets as follows:

a) The truth of misery (“dukkha”),

b) The truth that the misery originates from the craving for pleasure,

c) The truth that this misery can be eliminated,

d) The truth that this elimination results from a methodical way that must be followed. This

depends on an understanding of the evolution of a person’s psychosocial development.

6) THE LAW OF DEPENDENT ORIGINATION:

This law explains how every condition is interdependent on another prior condition. He stated that the original condition is ignorance (avijja); next is the cooperating karmic agents (i.e. mental qualities, dispositions and habits); then consciousness and then “name and form” (the naming and materiality of things). The next in line are the five sense organs and the mind; these in turn “condition” contact. This contact leads to the psyche, mental or emotional responses to sense objects (vedana). These objects lead to craving, the grasping for and attachment to the objects. This attachment determines “bhave” (or coming into existence) and hence “jati” (birth). The birth ultimately leads to old age, misery, death and so on….The Buddha includes the present day ignorance to the cooperating karmic agents from inheritance from the past. Solitary meditation by the Buddhist aspirant is an essential and fundamental means to understand this dependent origination. Likewise, present day karmic charge is believed to project into the future. Thus the dependent origination takes men into space and time, with the consequence of birth and death cycles.

7) EIGHTFOLD PATH:

The Buddha contemplated this “Eightfold Path” as the means to escape the above cyclical events. Ethical conduct has a major role in this purification process. With sincerity, reinforced by continued meditation, the Buddhist aspires to be liberated. The essentials of the “Noble Eightfold Path” are:

i) the right mode of seeing things (right view),

ii) right thinking,

iii) right speech,

iv) right action,

v) right mode of living,

vi) right effort in every mode of being,

vii) right mindfulness,

viii) right meditation or concentration.

8) NIRVANA:

Every Buddhist aspires to be rid of the delusion of ego, free oneself from the fetters of this world, thus overcome the repeated rounds of rebirths. This state of “Enlightenment” is a goal, not a “heavenly world or paradise”. To put it another way, the Buddhists aim to extinguish the fire that accompanies living; the fire of illusion, passion and craving. They search for not just the cessation of this fire but for the eternal, the immortal. Nirvana is thus explained as an ideal state, as ultimate bliss.

The ultimate explanation is offered by the Buddha himself in his inimitable language:

“There is an unborn, an unoriginated, an unmade, an uncompounded; were there not, there would be no escape from the world of the born, the originated, the made, the compounded.”

NB: When words in italics appear in the text, within parentheses, they are Sanskrit words accompanying the English translations.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

1) Encyclopedia Britannica, 18th ed. 1989, Vol. 15, pp 274-76

2) www.san.beck.org/EC9-Buddha.html

3) www.nationmaster.com/encylcopedia/Buddhist

3) BUDDHISM - A WORLD RELIGION:

THERAVEDA BUDDHISM

Gautama the Buddha did not claim to be divine or even as a prophet. He did not even invoke an omnipotent “God” or require his followers to worship him. Instead, he encouraged them to follow the “Dharma” that he preached. At the time of his death the Buddha did not name a successor and thus the democratic principles followed by the “Sangha” (community) guided the organizational hierarchy of the emerging religion. Nevertheless, in due course of time his followers did begin worshipping the Buddha himself, no doubt due to the human need for devotion to a savior-deity. There was also born the “Three Refuges” that all branches of Buddhism follow:

"Buddham-Saranam Gatchami (Vow to take refuge in the Buddha)”

“Dharmam-Saranam Gatchami (Vow to take refuge in the Dharma)”

“Sangham-Saranam Gatchami (Vow to take refuge in the Sangha)”

PANCHA SILA OR DASA SILA: (The five and ten precepts)

The Pancha Sila are meant to guide the moral obligations of laymen. These are “prohibition of killing, stealing, engaging in sexual misconduct, lying and drinking intoxicating liquor”. The five additional precepts (which the monks are required to follow) are “not to eat during prohibited hours, not to take part in festivals and amusements, not to use garlands, perfume or ointments, not to use a bed (or chair) that is too large or luxurious and not to use money (for oneself). This distinction between the lay followers and monks and members of the Sangha and non-Buddhists is in contrast to the Buddhists not recognizing caste, social class or ethnic origin.

THREE BUDDHIST COUNCILS:

Soon after the Buddha’s death a ‘council’ was called at Rajagraha with 500 “Arhats” (monks) in attendance. There they developed a “vinaya” (monastic discipline) under the leadership of the monk Upali and the “dhammas” (the sutras) under the leadership of the monk Ananda. A second council was called at Vaisali; this one was contentious and resulted in an apparent split between strict followers of the Buddha’s teachings and others who wanted to relax the rules. The third council was called by King Ashoka at Pataliputra (Patna) in 250 BC. At this council the Tipitaka (Buddhist Canon) was completed. Following this Ashoka sent missionaries to all over India and abroad; he also erected “Ashoka Pillars” with inscriptions on the pillars outlining the pursuit of Dharma and just living according to the Buddhist doctrines, all across India. However, a serious split arose between the Buddhist communities, involving the “Sarvastivadins” and the “Theravadins” over the former block’s belief of the reality of the past and future states of consciousness and which the latter condemned. The ‘Sarvastivadins’ (those who believed that ‘everything’ exists i.e. Space, past, present, future and Nirvana) were the fore runners of ‘Mahayana’ faction of Buddhism; whereas the ‘Sthaviravadans’ or ‘Sautrantikas’ (who favored the ‘Sutras’ over ‘abhidharma’ or higher dharma) evolved into the “Hinayana” faction. Over the centuries several smaller factions of Buddhists have evolved but our discussion will focus on these two predominant factions. The Theravada (Sthaviravada) spread from India to Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and the South East Asian countries. They were called “Hinayanans” by the more numerous Sarvastivad followers (“Mahayanans”).

THERAVADA (STHAVIRAVADA):

Theravadians follow the original Pali Canon of ancient Indian Buddhism. This is the school that Emperor Ashoka spread to Sri Lanka (Ceylon). From there this form of Buddhism spread to the South East Asian countries such as Myanmar (Burma), Cambodia, Laos and Thailand.

In this form of Buddhism, the followers are not concerned with metaphysical problems but with day to day psychosomatic interrelationship and cultivating ways of arriving at the state of an “Arahant” (“worthy one”). The ultimate aim is to pass from the temporal to the atemporal phase and overcoming the cycles of rebirths, i.e. a path to enlightenment. Seven factors of enlightenment and fours subsidiaries are recommended:

SEVEN FACTORS OF ENLIGHTENMENT:

1) Clear memory,

2) Exact investigation of the nature of things,

3) Energy,

4) Sympathy,

5) Tranquility,

6) Impartiality and

7) A disposition for concentration.

FOUR SUBSIDIARIES:

1) Love for all living creatures,

2) Compassion,

3) Delight in that which is good or well done and

4) Impartiality.

STAGES OF ARAHANTSHIP:

Those who believe in the teachings of the Buddha pass through these four stages:

1) One who has joined the stream and begun the process towards release from rebirth,

2) The next stage is where one only returns once,

3) The third stage is that of one who does not return again.

4) The stage of the arahant; one who has gained freedom from death. He is free from all bonds,

desire for existence, ambition and ignorance.

THE BUDDHA:

The state of the Buddha, the perfectly Enlightened one is “Nibbana” (Sanskrit Nirvana) from which one does not return. There are two kinds of Nirvana. One is achieved by the Buddha while he is still alive but after expending all karma. In the other, the Buddha dies and enter the Nirvana without remains.

THE PALI CANONS: (Early Buddhist Sacred Literature)

This is the Pali “Tipitaka” or “The Three Collections”: There is no parallel collection in Sanskrit. The three “Baskets” containing the 32 texts of Pali Canons are:

a) Vinaya Pitaka (“Basket of Discipline”),

b) Sutta Pitaka (“Basket of Discourse”) and

c) Abhidhamma Pitaka (“Basket of Scholasticism”).

A) VINAYA PITAKA:

This further divided into 3 divisions:

i) Sutta-Vibhanga (“Division of Rules”): These describe the obligatory rules and consists of

the Bhikku-patimokkha (“Rules for Monks”) and Bhikkuni-patimokkha (“Rules for Nuns”).

ii) Khandhakas (“Sections”): These have two parts: the Mahavagga (“Great Grouping) and the Cullavalgga (“Small Grouping”). These are rules of ordination and deal with “observance” days, descriptions of rainy-season retreats, clothing, food and medicine, judicial rules etc.

B SUTTA PITAKA:

These contain the discourses of the Buddha and are contained in five nikayas (“collections”). These start by the affirmation “Thus I have heard” and then mention the place and the occasion of the discourse. Although these may not represent the exact words of the Buddha, they do provide an insight into his didactic technique and show the richness and beauty of the illustrative similes.

i) Digha Nikaya (“Collection of Long Discourses”): This collection contains 34 Suttas and are divided into 3 books. These contain many doctrinal and philosophical ideas and ascetic practices and are peppered with similes and examples from every day life of ordinary people.

ii) Majjhima Nikaya (“Collection of Medium-Length Discourses”): This Nikaya has 152 Suttas (222 in the Chinese version). Like the Digha Nikaya, this collection is written in great poetic style and illustrated with similes.

iii) Samyutta Nikaya (“Collection of Kindred Discourses”): This has 2941 Suttas, in 59 divisions and grouped in five vaggas (parts). The first vagga has stanzas in the form of questions and answers. The second vagga deals with the principle of dependent origination. The third vagga deals with the doctrine of anatman (“nonself”). Fourth vagga deals with the transitoriness of the elements constituting reality. The fifth vagga consists of general discursion of the basic principles of Buddhist philosophy and religion.

iv) Anguttara Nikaya (“Collection of Item-More Discourses”): In this Nikaya there are 2308 small suttas organized into 11 groups. The discussions range from the training for good conduct, concentration and insight; eight worldly concerns of gain, loss, fame, blame, rebuke, praise, pleasure and pain. Here too similes enliven the discussion of such serious topics.

v) Khuddaka Nikaya (“Collection of Small Texts”): There are a total of 15 titles that range from a book for use by primary trainees, “Verses on the Dhamma”, “Utterances” (80 in all of the Buddha, “Hymns of the senior Nuns” and so on and so forth. The most important is “Suttanipata” (Collection of Suttas) and written in prose and in verses of considerable poetic quality.

C) ABHIDHAMMA PITAKA:

Only the Pali version of Abhidhamma Pitaka will be discussed here as that is the one that is followed by the Theravada school. This can be broken down to seven works:

1) Dhammasangani (“Summary of Dharma”) deals with the constituents of reality,

2) Vibhanga (“Division”): an elaboration of those constituents from various points of view,

3) Dhatukatha (“Discussion of Elements”): a classification of the elements of reality according to

various levels of organization.

4) Puggalapannatti (“Designation of Person”): Psychological classification of people according

to their intellectual acumen and spiritual attainment.

5) Kathavattu (“Points of Controversy”): This deals with doctrinal differences between various

denominations of Buddhism; it does deal with the movement that later became known as

Mahayana.

6) Yamaka (“Pairs”): Basic sets of categories arranged in pairs of questions.

7) Patthana (“Activations”): Discuss 24 kinds of causal relations.

A discussion of Pali literature in Theravada Buddhism cannot be considered complete without mentioning four great authors. These are 1) Nagasena: (~ 150 BC), who is credited with debates with the Greco-Bactrian ruler Menander and with the great literary work Milinda-panha.

2) Buddhagosa (AD 400): who had written the whole compendium of “Visuddhi-Magga (“Way to purity”) which deals with the whole Tipitaka. He also wrote commentaries on the vinaya, all principal nikayas and on the seven books of Abhiddhamma Pitaka.

3) Buddhadatta (a contemporary of Buddhagosa): He wrote a summary of the older commentaries on Abhiddhamma Pitaka. He reduced Buddhagosa’s five elements of metaphysical ultimates i.e. Form, feeling, sensations, motivations and perceptions to only four: mind, mental events, forms and Nibbana. 4) Dhammapala wrote commentaries on all the work not treated by Buddhagosa.

MAHAYANA BUDDHISM

by Prof. Roy J. Mathew

In 483 BC, at the age of 80, the great Buddha died in Kusinara, a small Indian village. After 6 years of strict asceticism the compassionate prince who abdicated his kingdom in search of an answer for the miseries of human existence- decay, disease and death- accomplished his mission. Seated on a bed of grass he spent seven weeks under the Bodhi tree (tree of enlightenment), determined not to stir till he attained the “supreme and absolute wisdom.” The Buddha had a transcendental experience of Reality through which came the answer to his quest. He dedicated the rest of his life to sharing the results of his search with others. Since then countless people in India and beyond have found relief, solace, and freedom through the great teacher’s influence.

After he renounced the material world at the age of 29 the Buddha remained totally focused on the subject of his quest, an answer to human suffering. He was not interested in deeper philosophical issues; he did not care about the existence or non-existence of God, in the creation or destruction of the universe, or in the meaning and purpose of life. When confronted with broad philosophical questions he chose to remain silent. Once one of his disciples threatened to leave his group if he did not answer one such question. The Buddha reminded him that he never promised anyone that he will provide answers to such questions but that his only promise was to provide a solution for human suffering. On another occasion the leader of a religious sect insulted one of the Buddha’s followers. Alone the Buddha went to see him. The man was afraid that entering into a discussion with the great Buddha might result in his defeat and the break up of his group. The Buddha assured him that that he was not trying to recruit disciples and that he only wished to show him and his followers a way out of human misery. The Buddha’s silence on key philosophical issues is well known (avyakrta). While we do not know for sure why he chose to remain silent there are a few clues.

Ananda , Buddha’s cousin and favorite disciple, was disturbed by the Buddha’s refusal to respond to questions from Vacchagotta, a revered “wandering” philosopher. The Buddha consoled Ananda by saying that there were no simple answers to these questions and that any attempt at responding to these questions would only lead to misunderstandings and even more and not fewer questions. As my friend Raghuprasad, the Editor of the series, asked me; is it possible that the Buddha did not know the answers? We do not know for sure.

Once, in autumn, when the Buddha was in the forest with his disciples, he picked up a handful of leaves. He told them that the information he had given them could be compared to the leaves in his hand; the leaves on the ground represented the issues he had not spoken of.

In Buddha’s days (and before and after) Indian philosophers loved to sport in intellectual gymnastics. Kings reveled in such exercises and patronized them. They organized debates to which leading philosophers, primarily if not exclusively Brahmins, were invited. The winners were rewarded with monetary gifts and titles and at times, permanent seats in the king’s court. Although the Buddha was willing to respond to questions from different kings such as Bimbisara, he actively avoided debates. He was humble, non-pretentious, and not greedy for fame or riches. He was simple in his life style and demeanor. He had no interest in competing, winning, or losing. He had no use for money and power. Because of his abhorrence for debates, unfortunately we do not know his position on various complex existential, religious, and philosophical issues.

The Buddha did not conceptualize his movement as a religion. In fact he was firmly opposed to religions with a canonical base, rites and rituals, priests, and gods and goddesses. He did not favor a “one size fit all” approach. He was sensitive to the differences among people in their intellectual capabilities, capacity for insight, and philosophical acumen. He did not give identical sermons to all audiences and the same lessons to everyone. While the basic ideas conceptualized in the four noble truths and the eight fold path of Buddhism remained the same, the message varied in the finer details depending upon whom he was addressing. The Buddha’s last message was to work out “your own salvation with diligence”.

The unanswered questions obviously caused cracks and crevices in the body of his movement (sangha). However, while he was alive faith in, and love and respect for, the great teacher filled in the fractures and fissures. With the Buddha’s demise the hairline cracks expanded into large canyons that eventually fragmented Buddhism.

The Buddha anticipated his death. However, he did not leave a comprehensive body of his teachings. The Buddha did not name his successor and did not leave any instructions regarding the sangha’s (group’s) future.

A few years after the Buddha’s death, some 500 of his followers under the leadership of Maha Kasyapa gathered in Rajagraha, a village in the modern Indian state of Bihar. This meeting is often referred to as the First Buddhist Council. During the First Council, some of the basic underpinnings of the movement were worked out. The texts that Kasyapa, Upali, and Ananda, who were close to the great teacher put together (namely, Abhidhamma pitaka, Vinaya pitaka, and Sutta pitaka, respectively) were canonized. Practices and principles they came up with were accepted as fundamental tenets. Although a number of disciples did not agree, they were overridden and firmly silenced. The new leaders seemed to have lacked the humility, compassion, and love that the great teacher possessed.

In 380 BC, a second Council was convened in Vaishali, north of the modern Indian city of Patna. By then the voices of dissent that were hushed up during the first Council, had grown louder and stronger. The “elders” still wielded a great deal of authority, and they had the power to excommunicate the liberal rebels which is what they did.

Significant disagreement existed on several points between the conservative group and the “rebel” group. The conservatives regarded some of the rebel practices as reprehensible. This included accepting money in the place of food during begging, eating after noon, following improper procedures (such as questioning the “elders” in meetings), enlightened monks having “wet dreams”, enlightened monks having doubts (they were supposed be omniscient not needing further direction), enlightened monks going to other people for information instead of relying on their own inner experiences, people making exclamations during meditation, etc. Most importantly, the rebels were unwilling to accept the authority of the Council of Elders who claimed total, unquestioned, and absolute authority. The conservatives called their group “Sthaviravada” or “Theravada”. The other group named themselves “Mahasanghikas”, (as they were larger in number) which subsequently became “Mahayana”. The Mahayana group referred to the traditionalistsas “Hinayana” meaning the “small, inferior vehicle or vessel”. The term is to some extent pejorative and not accepted by some conservatives. Mahayana, on the other hand, meant “the larger, greater vehicle or vessel”.

Theravada literature is less controversial and much better established. Almost all of the Theravada literature is in the ancient language, Pali. They are organized into three “pitakas” (baskets): Vinaya, Abhidhamma, and Sutta. They were reduced to writing only in 80 BC in Sri Lanka during the reign of Vattagamani, although they came into being at a much earlier date.

The Mahayana literature is mostly in Sanskrit. The group did not canonize any text. For a long time much was not known about the Mahayana literature, at least in India. The vast majority of Mahayanis accepted Theravada literature as authentic. However, they insisted that these teachings were “inferior”. They argued that the Buddha reserved those for people with inferior intelligence and capability to grasp complex philosophical issues. On the other hand, the Mahayana teachings were set apart for those with superior spiritual acumen and intelligence. Obviously, the Theravada followers did not and do not see it in the same light. The Theravadis, on the other hand, called the Mahasanghikas, “Papabhikshus” (sinful mendicants).

The Mahasanghikas held a council of their own known as Mahasangiti which, according to the Theravadis, “destroyed the spirit of the Buddha’s teachings”. By the time of the Second Council, Buddhism had fractured into some 18 separate groups each claming to be the “true Buddhism”.

Unfortunately, much of the early history of Buddhism is shrouded in myth and mystery. The picture changed drastically when Ashoka, the Mauryan emperor, espoused Buddhism. Ashoka, often known as the Constantine of Buddhism, became emperor around 250 BC. He introduced the art of writing on a larger scale and he left a legacy of philosophical edicts carved on stone and on granite pillars all over India. In 241 BC the third Council met in Pataliputra, Ashoka’s capital, under Tissa, son of Moggali, one of the “elders”. The main goal was purification of the Theravadi doctrines, namely the three pitakas.

Ashoka attempted to unify Buddhism but was not very successful at it. While he did not favor any one sect, he seemed to be more favorably disposed to the conservative Theravada over the more liberal and innovative, Mahayana. Under Ashoka, Buddhism took root and grew by leaps and bounds. It eclipsed the Brahmanical Hinduism, and Buddhism became the dominant religion in India. Ashoka wanted Buddhism to become a world religion. He certainly took it all over his empire from Kabul to the springs that fed the Ganges and from the snow capped Himalayas to the Vindhya Mountains. Emissaries were dispatched all over India and beyond. According to the thirteenth edict, Ashoka’s missionaries went to Antiochus II of Syria, Ptolemy II of Egypt, Antigonos Gonatos of Macedonia, Magas of Cyrene, and Alexander II of Epirus. By the third century BC, Buddhism had found its way to Kashmir, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Tibet, China, Japan, and Mongolia. Buddhism held sway for nearly a thousand years before it started to lose favor in India.

After Ashoka, a number of the new rulers of India; the Yavanas, the Sakas, the Ksatrapas, the Satavahanas, the Pahlavas, and the Kusanas also adopted Buddhism. Several of these rulers were not of Indian extraction. The Guptas, who established authority in the first century AD, on the other hand, remained faithful to Brahmanic Hinduism.

From the rise of Buddhism to the time of Ashoka, the Theravada doctrine prevailed. From the time of Ashoka to the Kushana king, Kaniska (150 AD), a weakening of the Theravada doctrine occurred together with a growth of Mahayana Buddhism.

Theravada doctrine was icy cold and steel strong. It captured and preserved the monastic, puritanical, and moralistic elements of Buddhism. It called for rigid adherence to the doctrines of Vinaya pitaka (conduct and discipline) with a great deal of emphasis on the inner world and almost total rejection of the outer world. Only few could live up to its lofty expectations, and it was aptly named Hinayana Buddhism (only for a few). Unfortunately it lacked in the love, flexibility, and humility of the Buddha. The Buddha was very open and ready and willing to listen to the others and to change. For example, he accepted Ananda’s suggestion to include women in the sangha although initially he was opposed to the idea. The Buddha used to wash one of his disciples who had multiple malodorous skin ulcers, to dress him and to put him to bed every night. The other members of the sangha found the task too repulsive.

Theravada Buddhism, with its rigid requirements that only a few could follow could not sustain itself, eventually it accepted a lot of Hindu doctrines. The pendulum seemed to swing all the way to the other extreme. Concepts of hell and heaven were acknowledged. The Buddha was defied, several Hindu rishis (saints) were recognized as arhats (Buddhist saints) and finally, several Hindu deities became part of the Buddhist pantheon. In its final form it was virtually indistinguishable from other polytheistic religions.

As Theravada Buddhism was disintegrating, Mahayana Buddhism gained currency. Mahayana Buddhism owes its strength mostly to the intellectual genius of Nagarjuna, followed by Candrakirti and Aryadeva.

Nagarjuna lived in the second century AD. He was a Brahmin by birth and was born in Andhra Pradesh in South India. He converted to Buddhism. Nagarjuna was endowed with an unusually keen intellect, in - depth knowledge of philosophy and an incisive ability to reason. Nagarjuna was largely responsible for the perfection of the Madhyamaka philosophy, which forms the cornerstone of Mahayana Buddhism. The Buddhas called his way “Madhyama Pratipad” (the middle path). Nagarjuna developed it further and called his philosophy “Madhyamaka”, “Madhyamaka-sastra” or “Madhyamaka-karika.” Aryadeva and Candrakirti provided further development and refinement of Nagarjuna’s philosophy.

A complete discussion of Mahayana Buddhism and its differences from the Theravada philosophy will be beyond the scope of this chapter. In time both schools of thought expanded and branched out. There are so many divergent philosophies on either side that make comparisons elaborate. However, it must be noted that they all share the basic fundamental principles that characterize Buddhism. In other words, one must not be carried away by the differences and overlook the similarities. The major differences between Mahayana and Theravada Buddhism in the earlier days are discussed below.

The early Mahayanis saw the Buddha as more than an individual. According to them, he was beyond matter, time and space, and totally transcendental. His human body was simply a shell created to accommodate the true Buddha who was supermundane.

Theravadins saw Buddhist saints (arhats) as perfect beings who were beyond the material world. The Mahayanis, on the other hand, did not see the arhats as perfect, although they had transcended the mundane world. They were subject to doubts and questions.

Mahayanis believed that empirical knowledge cannot produce insight into true Reality. Only experience that transcended materiality could generate a vision of the Real, which in essence is nothingness or sunyata. The Real cannot be spoken of as words.

Theravada philosophy argued that the personal self was not real but the elements (dharmas), which constituted the personal self were Real. Mahayanis did not accept this viewpoint. According to them, both the self and the elements (dharma), which constituted the self, were unreal.

Mahayana posits a single reality that is in excess of time and space. It cannot be thought of or spoken of, as it is anterior to both thought and language. Everything has its basis in the true Reality that is monistic The Real transforms itself into matter and the material world, and in the process acquires qualities. The material world is characterized by quintessence, attributes, and activities. A tree is made up of cells (quintessence), it is tall and green (attributes) and it grows and reproduces (activity). The Real, in which the tree has its basis is without quintessence, attributes, or activities. The Real is not born and it cannot die. The Real is nothing (sunyata) in a material sense and everything in a spiritual sense. Nirvana is release from the material world and identification with the Real that is nothing.

Within India Mahayana Buddhism overlapped with the several Upanishads,. While there is some controversy as to which one came first, most authorities seem to give precedence to Mahayana Buddhism. Gaudapada, the famed Indian philosopher, acknowledged in his karika that Buddhism was one of its major sources. Gaudapada adopted the metaphysical aspects of Mahayana doctrines and integrated it with his philosophy. Shankara ( 788-820 AD) is probably the best known and most influential Indian thinker since the Buddha. Advaita philosophy, Shankara is credited, with can be traced to Gaudapada. Shankara paid homage to Gaudapada as one of his gurus (teachers). The Nirguna Brahman of Advaita and the featureless Real of Mahayana Buddhism are almost identical. One of the great ironies of Indian philosophy is Shankara’s open hostility towards Buddhism. While accepting the metaphysics of Mahayana philosophy as the central feature of his philosophy he went all out to destroy Buddhism. This did not go unnoticed. Later Hindu philosophers, notably Ramanuja, called Shankara, “Prachanna Buddha” (Buddha in disguise).

Bodhgaya is one of the most sacred places of Buddhism. After years of intense search it was here that the Buddha found the final answer. Buddhism was born here. While seated under the Bodhi tree the Buddha found the answer to the question that plagued him; a remedy for human suffering. He had a vision of the Ultimate Reality with which came the answer to the question. In Bodhgaya, sites of historical significance to the student of history and of religious significance to the devout Buddhist are identified and marked. These places are frequented by pilgrims from India, Tibet, China, Myanmar, Thailand, Japan, and elsewhere. In all these places the pilgrims also see slabs of black stone that carry symbols of Hinduism. I was given to understand that they were placed there by Shankara. We do not know if Shankara was motivated by his respect for the great teacher, whose teachings formed the basis for his Advaita philosophy, or by his hatred for an individual who was responsible for the decline in Hinduism in India for over one thousand years or perhaps both.

India is known for its religious tolerance. I do not know what motivated Shankara to engage in such an activity, and I do not know what caused him to be so confused. However, as a person who holds Shankara in high esteem, as an admirer of the Advaita philosophy, and as a Malayalee who considers it a great honor to be born in the same place as Shankara, the stone slabs hurt me deeply and befuddle me profoundly.

While Shankara did contribute to the demise of Mahayana Buddhism in India, changes that took place within the movement itself had more to do with it. First and foremost, Mahayana metaphysics and Hinduism (Mandukya Upanishad, Gaudapadakarika, Advaita, etc) became inseparable. At the theistic level, the Buddha became one of Vishnu’s avatars. Adi Buddha headed a series of divine beings and phenomena. When Mahayana spread to other lands and cultures it absorbed local beliefs and practices. Extravagant stories of superstition, paranormal phenomena, and sensuality became components of Mahayana. In some locations practices that involved the use of drugs (marijuana), sex, and miracle making became acceptable. While Mahayana Buddhism continued to flourish in the other locations, in its new form it became alien to India where it was born, and there it died a natural death.

Roy J. Mathew, MD

Clinical Professor of Psychiatry

Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center

Odessa, Texas 79763

Director Brain and Behavior Clinic

Marion

Midland, Texas